Evening and welcome to our final blog posting during this course. Throughout the course we’ve learned various methods in which to analyze data via code, and specifically Python and applicable libraries. As you read through this post you’ll notice a couple functions, multiple variables, and a statistical method of multivariate analysis to come to a final conclusion on the hypothesis.

Objective: Conclude how accurate can manually entered addresses via users and an ERP system compare, based on a popular address validation API according to USPS address standards. Additionally, what are some assumptions can we gather based on address metadata provided by the API.

GOAL: To provide an estimate on the accuracy of a current ERP address information within a specific region.

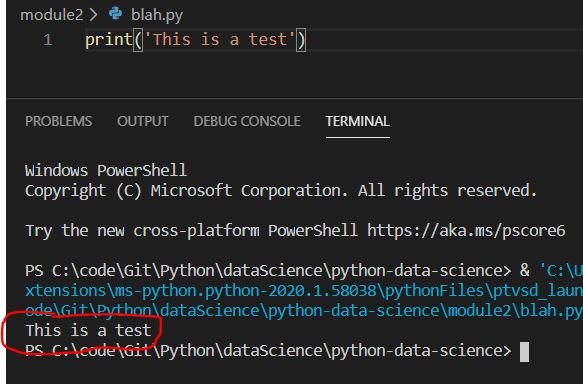

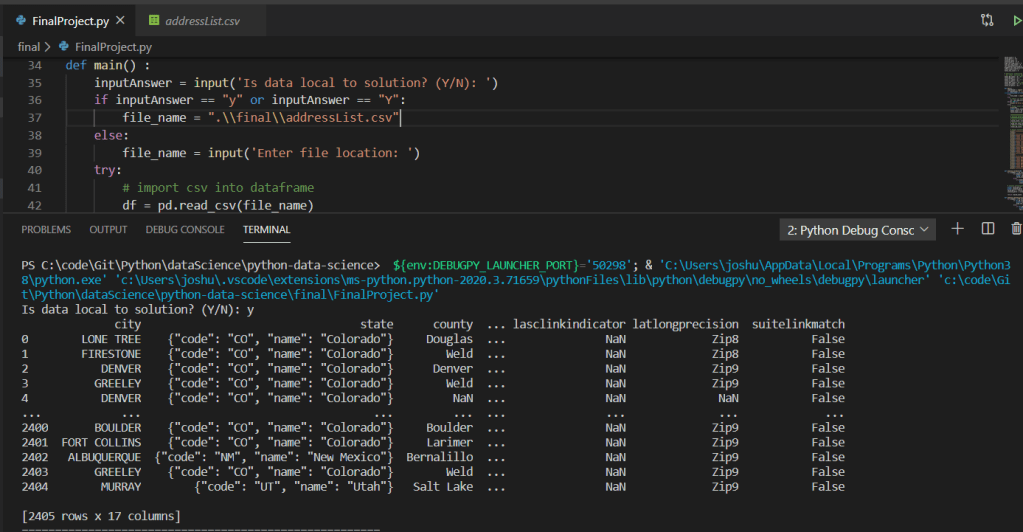

The program utilizes a simple .csv data file read into a dataframe utilizing the Pandas Python library. The data set consisted of approximately 2,400 address records. Below is a screen shot of the records output in the terminal:

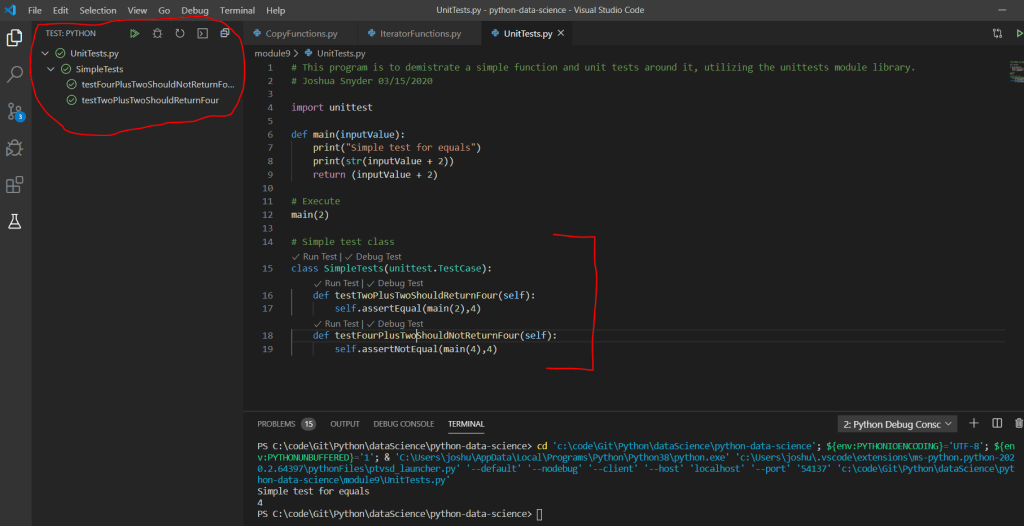

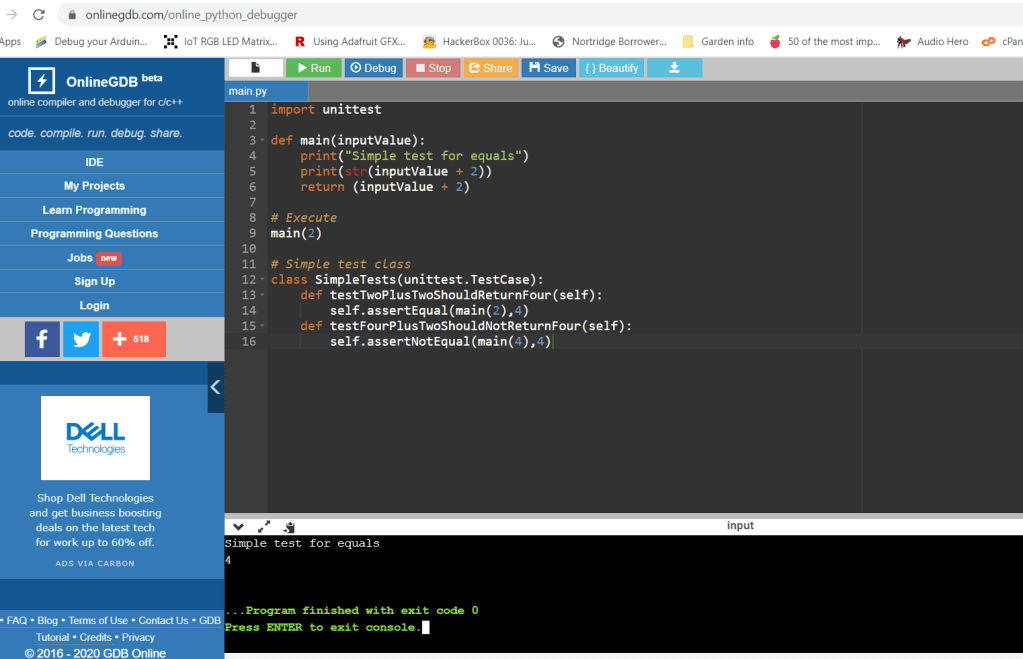

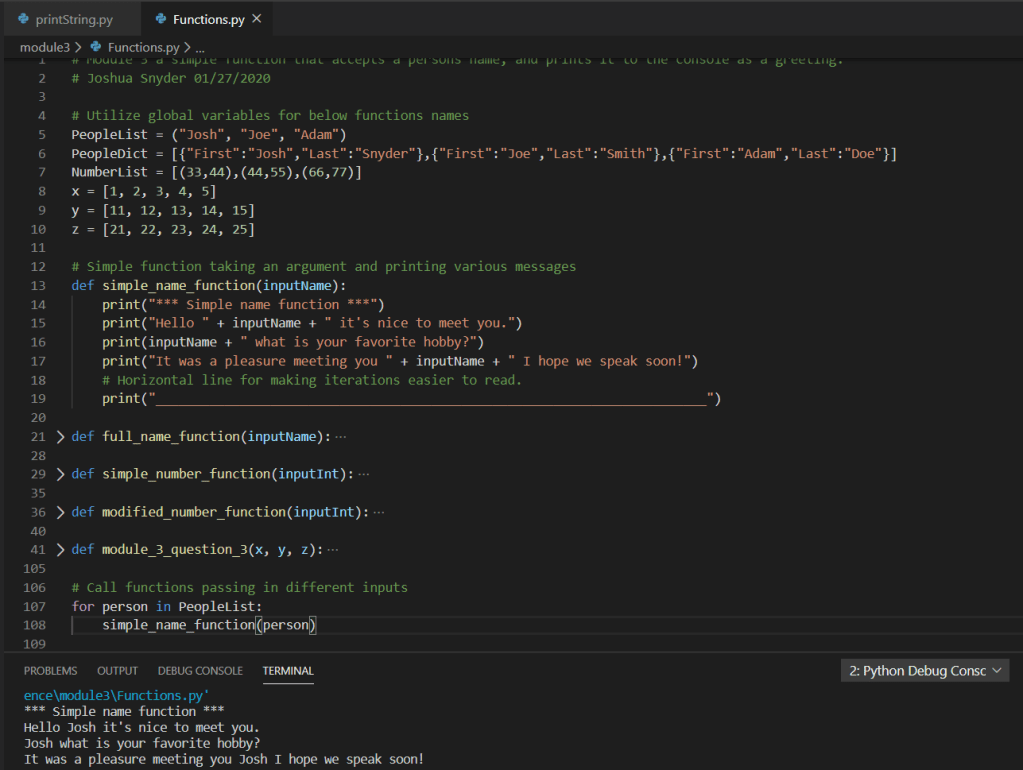

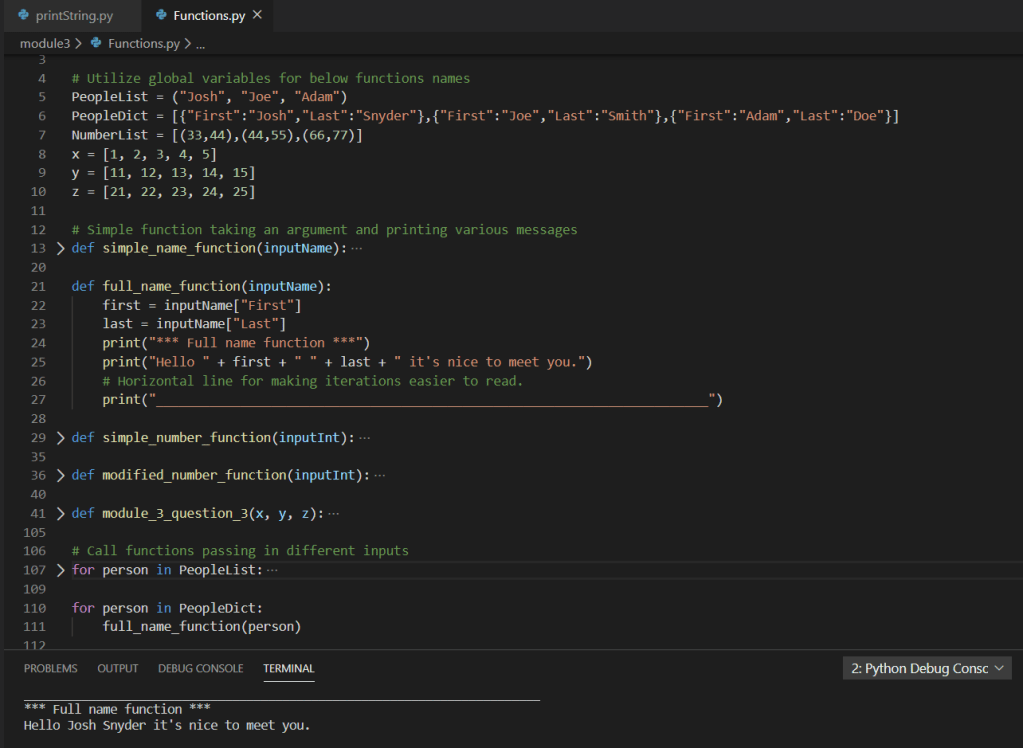

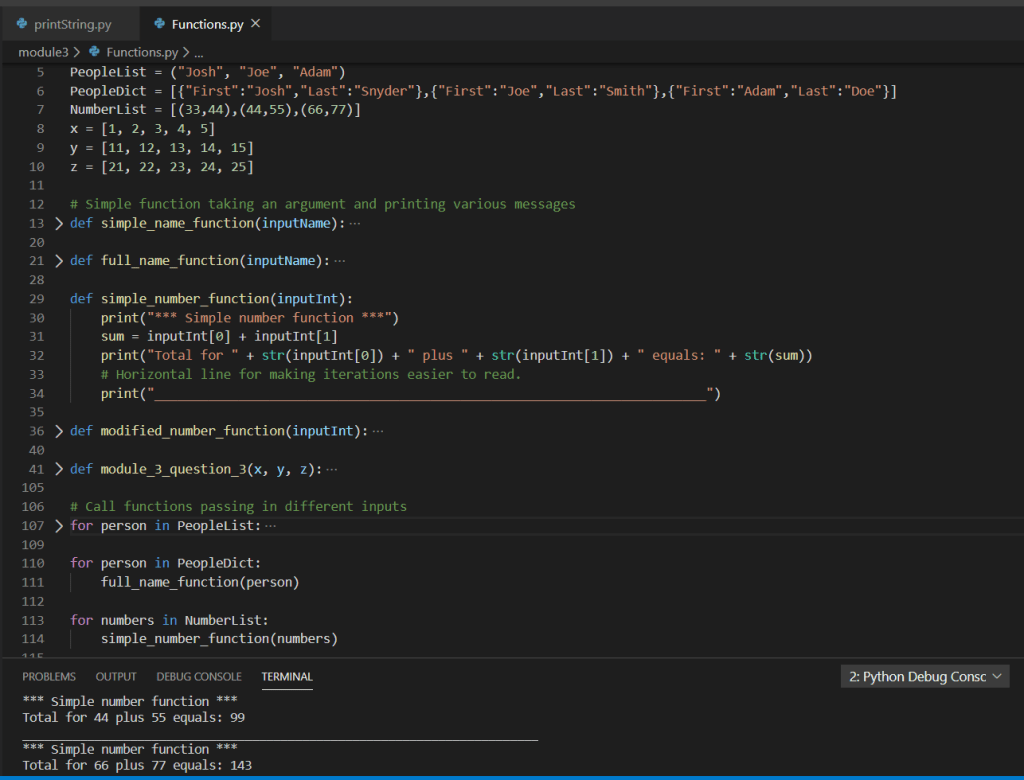

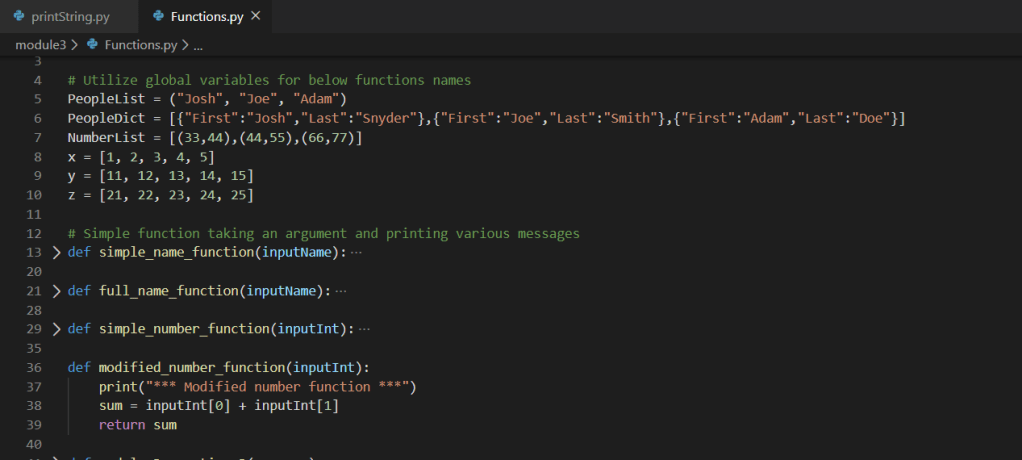

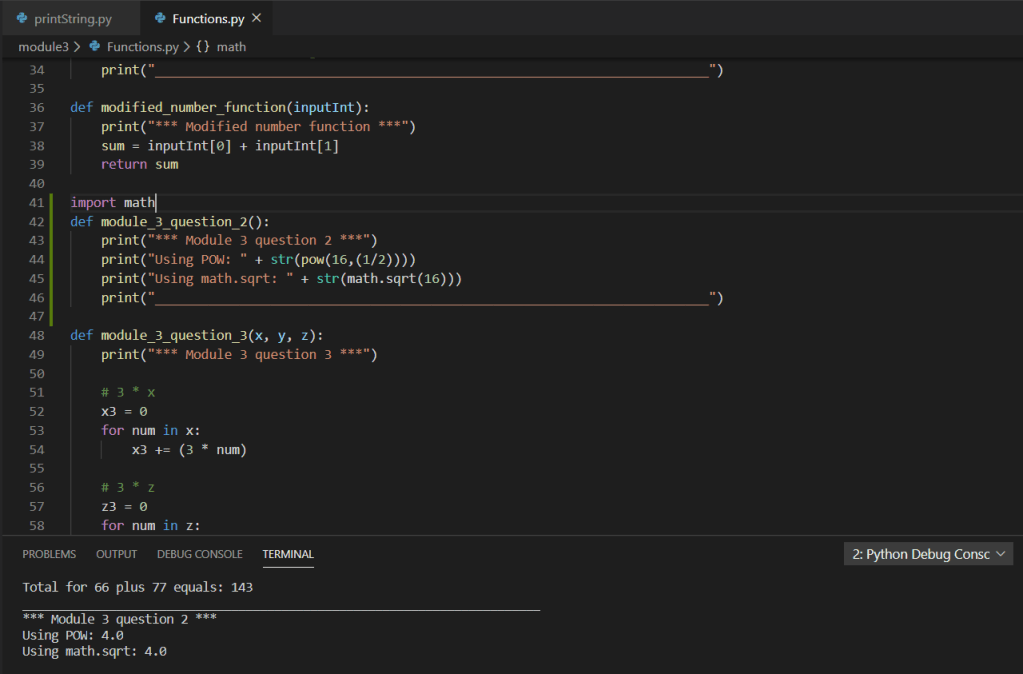

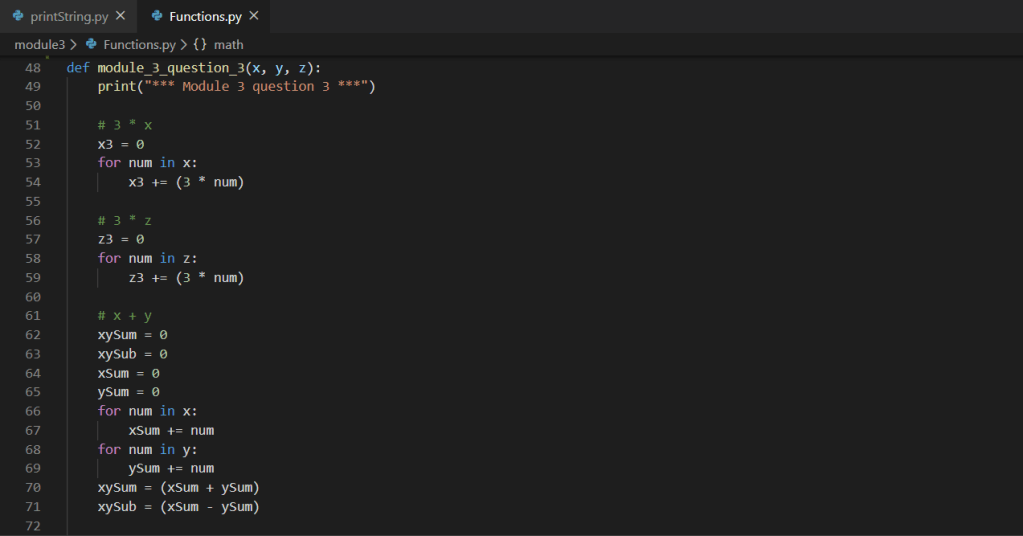

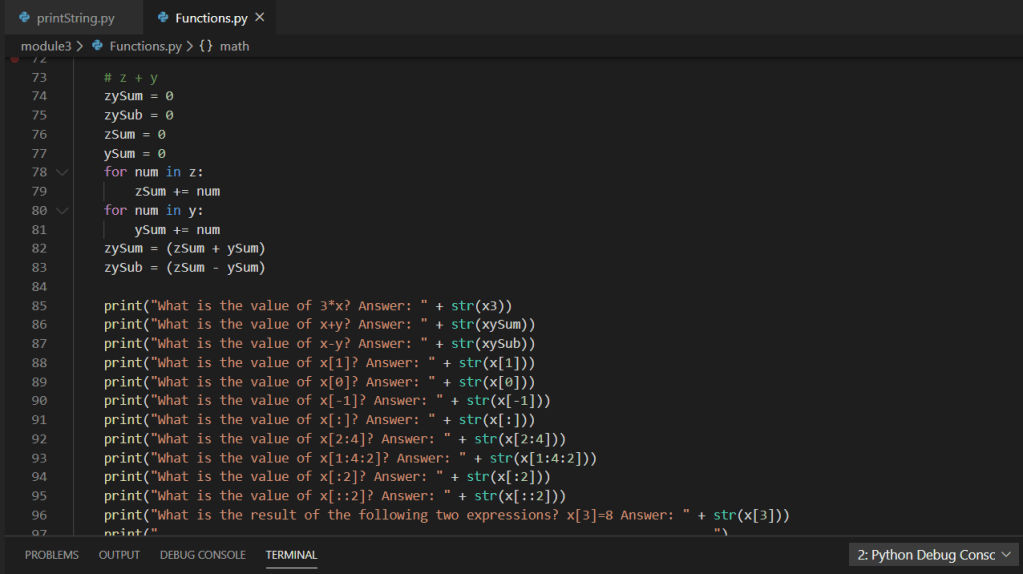

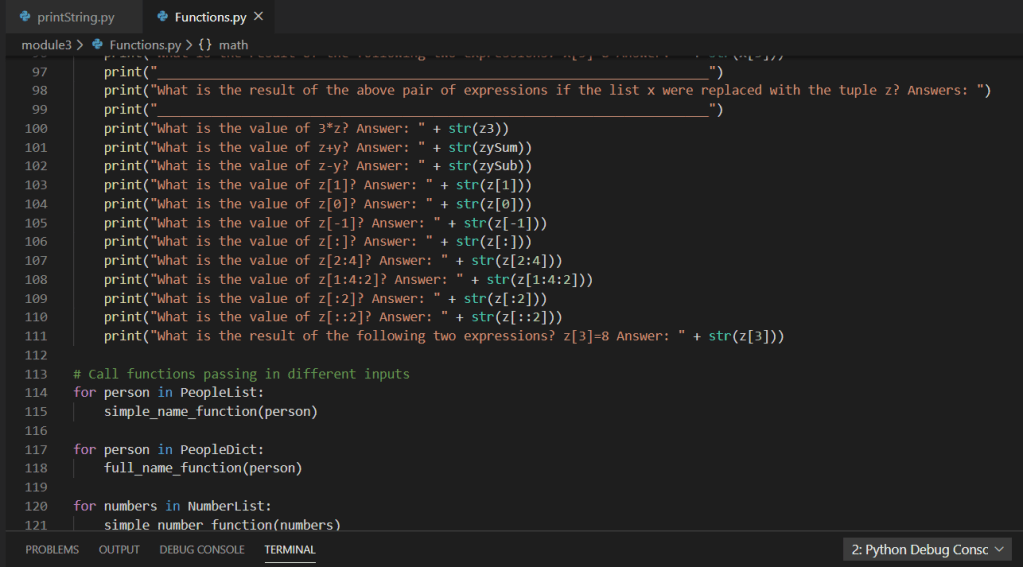

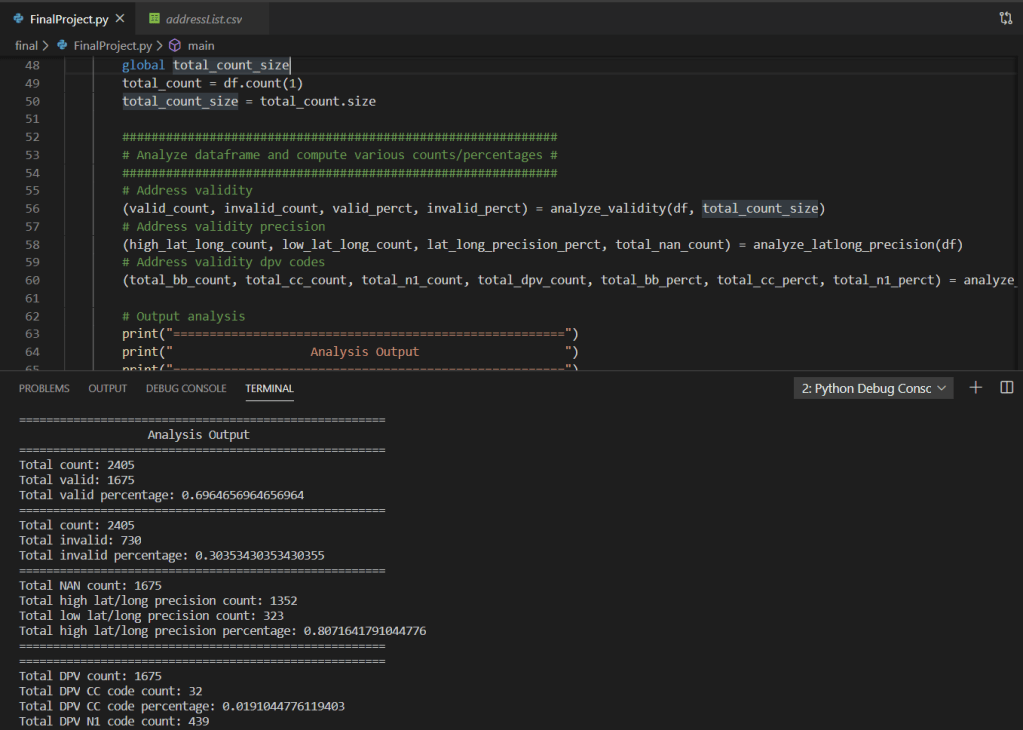

As we continue walking through the program we can see multiple functions accepting parameters and returning tuples utilized within the mainline of the main function:

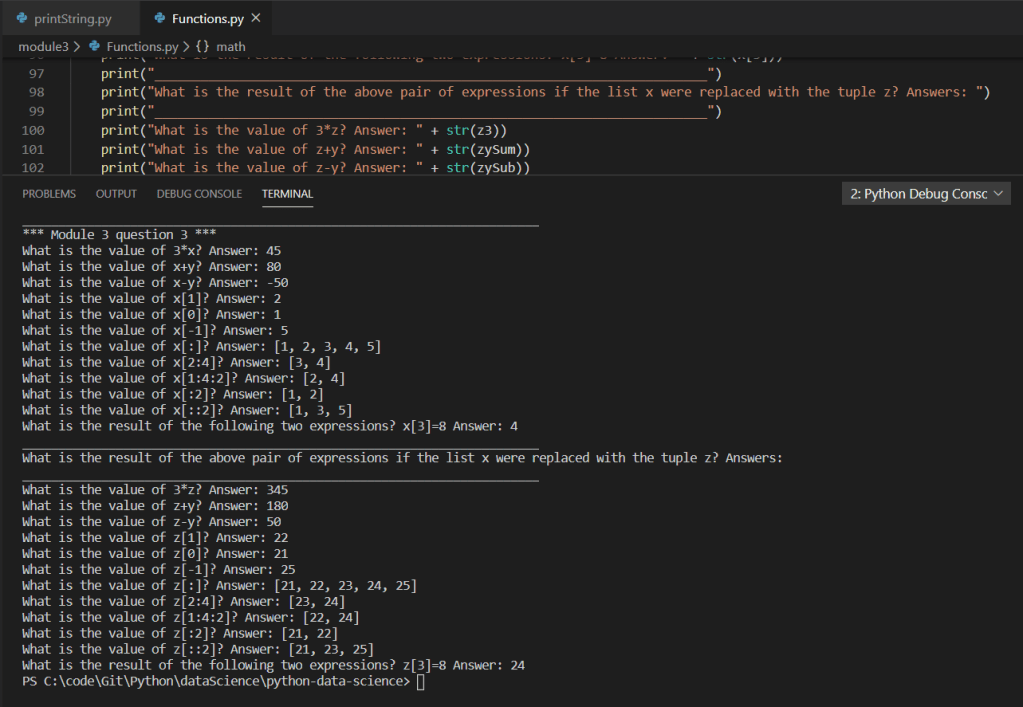

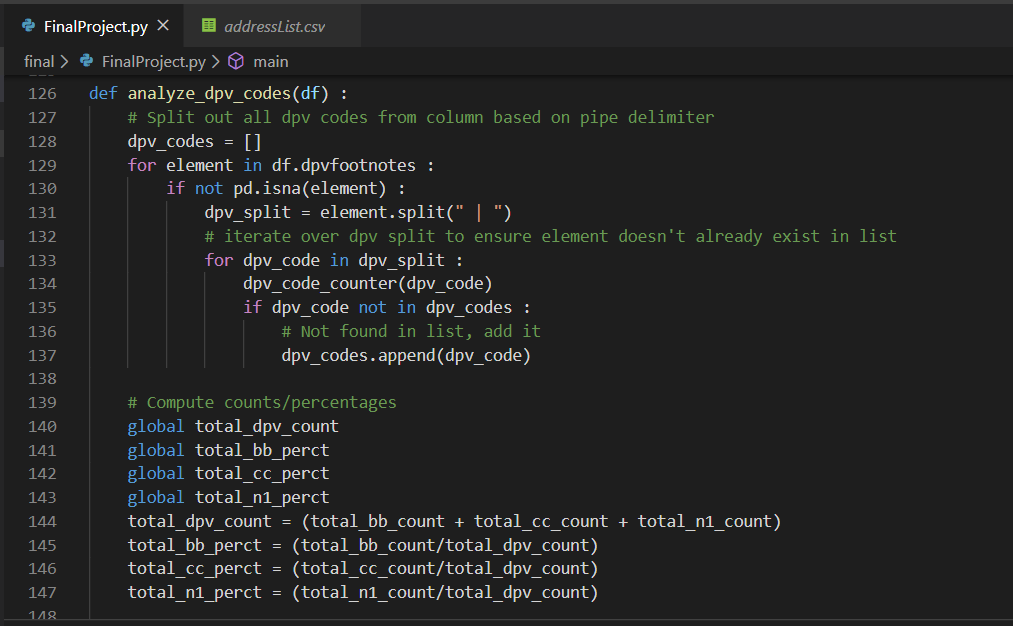

Based on the above screen shot, we can see various analysis output data points from the imported .csv via dataframe. Stepping into a single function for further review, we can see the use of various iterators (for loops), conditional statements (if statements), as well as the additional use of the Pandas extension method for checking NaN on the value of the variable within the iterators. Additionally, we can see the simple arithmetic to compute the total count as well as various percentages.

Furthermore, once multivariate analysis was applied across all percentage variants, the overall accuracy drops to approximately 40% as shown in the below screen shot:

In conclusion, we can say that the accuracy of manually entered addresses via users within a particular organization, for a particular region of the organization, when applied against a popular address validation API according to USPS address standards.

For the full code example and others like it, please feel free to check it out here: https://github.com/joshsnyder/python-data-science/blob/develop/final/FinalProject.py